This observation preceded his discussion of The Gentle Persuasion�: Bhoodan (pp 202-207), from which we quote excerpts below:

Almost on the heels of the zamindari abolition legislation came one of the most repressive phases in the history of the Bihar government. A Communist Plot was discovered and any attempt by the lower orders of the tenantry under-tenants and share-croppers and the agricultural labourers to organise themselves was seen as a sign of the Red Menace.A Public Safety Act was passed and its provisions were used to try to stop all mass movements of the peasantry.However, the more repression was intensified the stronger became the resistance by the peasantry and, in places, even a Telengana-type of insurrection started being planned out.

It was at that point of time that Vinoba Bhave who started his Bhoodan movement in Telengana intervened in Bihar also. In the beginning, his scheme of getting zamindars to voluntarily donate land for distribution among the landless seemed to have caught on. The peripatetic agrarian reformer attracted thousands wherever he decided to do his padyatra, and after a few years even the former fire-brand revolutionary Jaya Prakash Narayan was persuaded to give up active politics and do jeewan-dan (gift of life) in the cause of Bhoodan and Sarvodaya. With these two charismatic leaders in the forefront, it was believed that the movement would be able to generate enough enthusiasm to become a way of preventing the spread of communism and emerge as a method of bringing about a peaceful revolution.� To this end, Bhave resolved to remain in Bihar till the land problem was finally and completely solved. To solve the land problem in Bihar, Bhave estimated that he and his followers would need to collect 32, 00,000 acres of land. After two years of intensive Bhoodan activity in Bihar, Jaya Prakash Narayan announced in 1954 that the movement had not reached its target

By August 1954, the Bhoodan workers claimed to have collected 21, 02, 000 acres by way of actual gifts or promised donations, but the quantum was still much below the target even in 1956 when it was claimed that 21, 47, 842 acres had been collected.

By 31 March 1966 the Bhoodan Yagna Committee had to admit officially that its total acreage of land collections had not increased; instead, it had decreased from 21, 47, 842 acres in 1956 to 21, 37, 787 acres in 1966; of this at least 500, 000 acres, mainly contributed by the Raja of Ramgarh, was either forest land or legally contested lands. More damaging to the image of Bhoodan as a successful movement is the fact that by March 1966, Bhoodan leaders could claim to have distributed only 3, 11, 037 acres (less than 10 per cent of the announced target). Even such land as was distributed was at times waste land and, at least in one case, at the bottom of a river. The result was by no means a peaceful revolution,brought about by the Bhoodan movement or the legislative measure which institutionalised the movement in Bihar.

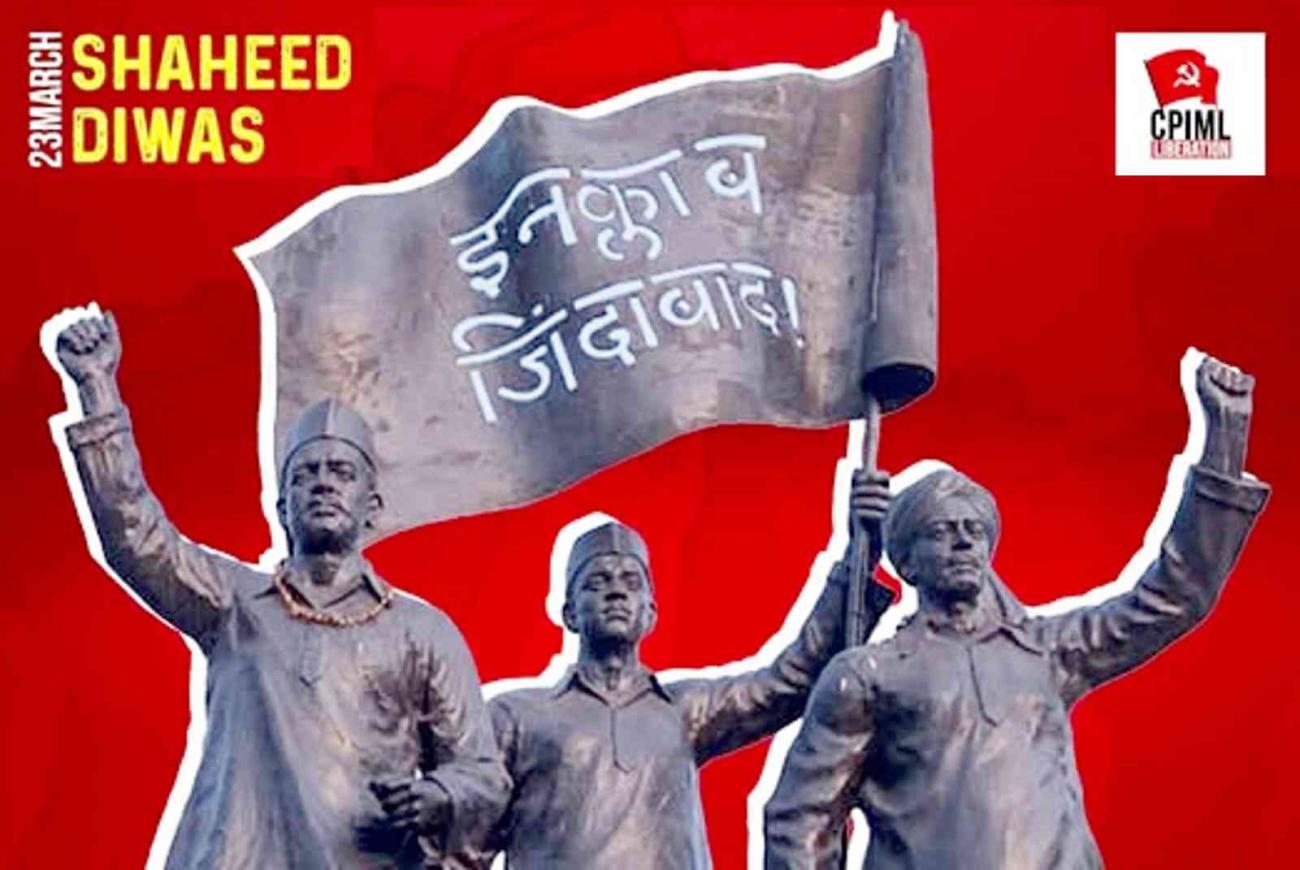

Box

From Flaming Fields

CPI(ML)s 1986 document Report from the Flaming Fields of Bihar identified Bhoodan and other similar measures as nothing but part of a wider counter-insurgency move to stamp out armed peasant struggle from the face of Bihar.� It quoted Badri Narain Sinha, DIG (Naxalite)s article From Naxalbari to Ekwari (The Searchlight, June 11-13, 1975): putting in zealous and dedicated social reformers drawn from all shades to bring about transformation on the socio-cultural planes is as much a part of the counter-insurgency measures as concentrated police operations or operations by the special task forces, may be from the supreme armed formation, the army itself.�